In a previous post, I covered two-fund portfolios and how to implement them. While there are good options available for making two-fund portfolios, the complexity involved with two in particular seems to make it a less viable solution than three-fund portfolios in many cases.

In this post, I want to cover one-fund portfolios. I don’t necessarily mean one fund in one account but having an integrated portfolio in each account that you may have between your current employer, any previous employer accounts that you’ve decided not to roll over, and any IRAs or taxable accounts you might have. (That taxable account part might get a little sticky!)

100% stocks?!

Sounds crazy, but there can be good reasons to go 100% stocks. For example, if you’re just starting out in your early twenties, you might consider going 100% stocks until some point when you have a considerable amount of principal to protect so long as you know you can take the hit in the event of a drawdown. It’s better to take the hit early and know how it feels in terms of your risk tolerance.

A weaker argument goes something like “The S&P 500 has never lost money over a twenty-year period,” thereby justifying holding 100% stocks until somewhere around age 45. Okay, that statistic is probably true, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be broken. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Also, the S&P 500 is not the entire stock market. Japan’s stock market only recently recovered from a drawdown that began in 1990. So this at least should accentuate the need to diversify internationally. And we shouldn’t forget that stocks are risky.

The other situation where 100% stocks might apply is when the investor simply has enough to knowingly take the risk anyway. The investor may for example be able to live off a severely diminished portfolio. A very aged investor may be investing in the interest of heirs rather than oneself.

But the risk of a 100% stock portfolio is not merely the risk of the stocks going down; it is the risk of the investor abandoning the plan due to the inability to handle the shock of a drawdown and then failing to take on subsequent gains. A blog post can never sufficiently assess whether you are ready for that kind of risk.

But if you think you are, and you want a one-fund portfolio, I would point you either to Vanguard’s Total World Index (VT) or Avantis All Equity Markets ETF (AVGE), both of which I covered in the post concerning two-fund portfolios and are diversified globally. (And as a matter of repeated full disclosure, I do not hold AVGE itself but do hold many of its underlying components.)

Target-date funds

Boring!

This is probably what most people think when they think of one-fund portfolios and for good reason. They are very common inside employer accounts and easy to find among IRA providers. They’re also reasonably easy to select and use: pick the one with the year closest to when you retire and call it a day.

But let me offer you some things to consider before you pick a fund family and a particular fund:

Is the current asset allocation something you would actually choose for yourself? Each target date fund at a minimum has to have a fact sheet that includes information on the mixture of stocks and bonds inside the fund. Most often, target date funds are “funds of funds,” so you’ll see the providers own funds inside. You may need to add up which funds are stock funds and which funds are bond funds in order to arrive at a stock-to-bond ratio. Remember that the stock side is liable to lose 50% in a drawdown, and the fact that you’re in a target-date fund does not insulate you from this. I also tend to suggest “age minus twenty” in bonds as a baseline asset allocation, but most funds for my age are about 90% stocks and 10% bonds. The fund companies have an incentive to be higher in stocks than what may be prudent because they want to outperform their peers’ funds.

Is the expense ratio worth the convenience? Some target-date funds are substantially more expensive than the funds inside them. For example, the Fidelity Freedom Index 2050 Fund (FIPFX) has an annual expense ratio of 0.12% despite that none of its underlying funds have expense ratios that high. You could effectively “plagiarize” the target date fund and pay less. In my own employer account, there is a difference in expenses but one so small that I don’t hesitate to recommend the target-date fund to my peers.

Is the fund family hiding something cheaper? Did you notice the term “Index” in “Fidelity Freedom Index 2050” there? Fidelity also offers Fidelity Freedom [awkward silence] 2050 (FFFHX) with a 0.75% expense ratio as a means of selling active management. Guess which one the Fidelity guy on the phone wants you to buy. Charles Schwab’s target-date funds do the same thing. There are even “blended” target-date funds that combine both indexing and active-management. If you are buying a target-date fund from either Fidelity or Charles Schwab, you will likely want to make sure they are fully “index.”

Fixed-allocation funds

Less boring?

If you want more control over your asset allocation but don’t want to manage four or more funds to seemingly get it global enough, a fixed-allocation fund might do the trick for you, but as with the target-date funds, they can involve additional expenses.

For example, Vanguard’s fixed-allocation funds (branded “LifeStrategy”) declare their target allocations right at you. Each fund is a mixture of U.S. stocks, U.S. bonds, international stocks, and international bonds. But they have not-so-great expense ratios ranging from 0.11% to 0.14%, more than what you could pull simply by managing equivalents of the four underlying funds yourself. These are also mutual funds rather than ETFs, so you may not be able to acquire them without opening an account at Vanguard and having to meet a $3,000 minimum investment.

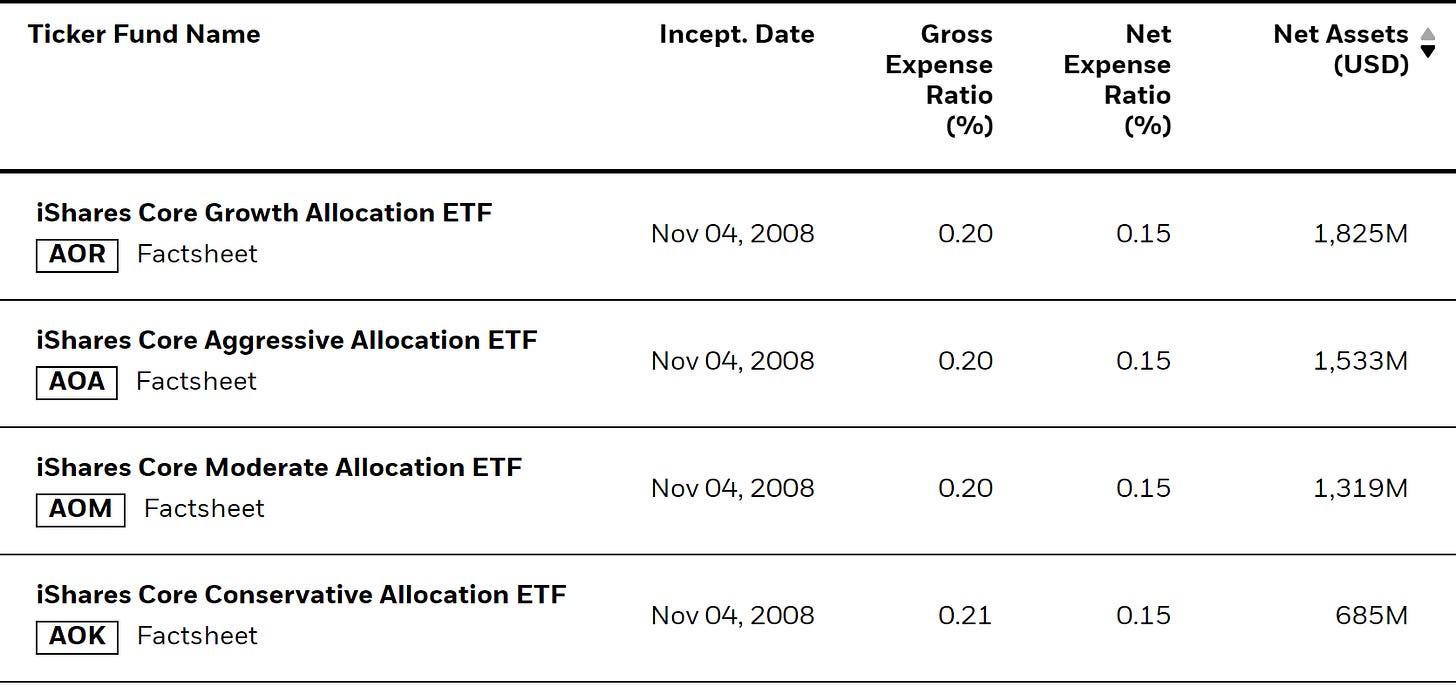

iShares offers its own range of fixed-allocation ETFs. Hooray for no minimums. But the website doesn’t tell you straight up what the basic stock/bond allocations are without digging and doing some math. “Aggressive” is about 20% bonds. “Growth” is about 40% bonds. “Moderate” is about 60% bonds. “Conservative” for some reason breaks the trend and has 70% bonds.

Warning: Taxes!

Let me put this bluntly:

Do not hold an asset allocation mutual fund (such as a target-date fund or a fixed-allocation fund) in a taxable account.

I am a simplicity advocate (though not a practictioner!), and let me say this again: do not hold an asset allocation mutual fund such as a target-date fund in a taxable account. Because these funds persistently rebalance, those rebalances buy and sell securities, and these can come with having to pay capital gains taxes just for sitting there and holding the fund.

In a worst-case scenario, it’s bad enough that Vanguard gets sued for mismanaging decisions that led to massive capital gains taxes for which investors paid the bill.

For reasons that are too complex to explain here, ETFs are unlikely to push capital gains (or at least substantial capital gains) to shareholders, so they’re probably not worth worrying about. But this isn’t the case with mutual funds. In other words…

Do not eat yellow snow.

If at first you do not succeed, do not try skydiving.

Do not hold an asset allocation mutual fund in a taxable account.

If you’re only investing inside tax-advantaged accounts, however, the account will shield you from these capital gains taxes when used correctly.

What is the convenience worth?

It depends on you and your situation. Pragmatically, I especially must cite situations where the investor may not have reliable internet access and therefore needs to put as much as possible on “autopilot.” For people in the military on deployment, I almost always will recommend the “L Funds” target-date funds within the Thrift Savings Plan. Psychologically, you may benefit from inhibiting yourself from messing it up.

Of course, this gets more complicated when you have multiple accounts. You may want an approach where each account has a single fund in order to keep your investing simple. In such cases, I would encourage you to make sure the single funds are at least similar to each other, as having to track multiple asset classes on a spreadsheet would completely defeat the point of single-fund accounts.

Finally, let me throw a rock, but not at you the reader. Occasionally I see it claimed that directing an investor towards a target-date fund or something very simple is dishonorable because it is in effect calling the investor stupid and unable to learn how to build an asset allocation. Hooey. We all come at this from different levels of knowledge, have different needs, and have different occupations and lives. If you find the need to have a one-fund approach, it is not dishonorable or stupid; it is simply adapting to your own needs. What is dishonorable is how much of the industry preys on people who would otherwise benefit from simple and sufficient approaches such as these.

Garrett O'Hara is not a financial professional, just a DIY investing enthusiast. This information is for your information and education only. Particular investments or trading strategies should be evaluated relative to each individual's objectives. Opinions stated constitute my judgment as of the date of when I stated them and are subject to change without notice and are provided in good faith but without responsibility for any errors or omissions contained therein. This information is supplied on the basis and understanding that I and my information sources are not to be under any responsibility of liability whatsoever in respect thereof. Get educated and make your own sound investing decisions.